In 1869, the Avondale Mine Disaster occurred in eastern Pennsylvania. After that incident, mining in Pennsylvania started to become more regulated. In 1870 the Anthracite Mining Act was passed to be followed in 1897 with the Bituminous Mining Act. As a result of these Acts, the Bureau of Mines was established under the Dept. of Internal Affairs.

The primary function of the Chief of the Bureau of Mines was to “devote the whole of his time to the duties of his office, and to see that the mining laws of this State are faithfully executed; and for this purpose he is hereby invested with the same power and authority as the mine inspectors to enter, inspect and examine any mine or colliery within the State, and the works and machinery connected therewith and to give such aid and instruction to the mine inspectors from time to time as he may deem best calculated to protect the health and promote the safety of all persons employed in and about the mines, and the said Chief of the Bureau of Mines shall have the power to suspend any mine inspector for any neglect of duty.”[1]

As part of the duties of the Chief of the Bureau of Mines was to report annually on the status of mines in the Commonwealth and to record accidents, fatalities, or other items of interest that are submitted to him by mine inspectors. These reports were made available to anyone who wished to view them.

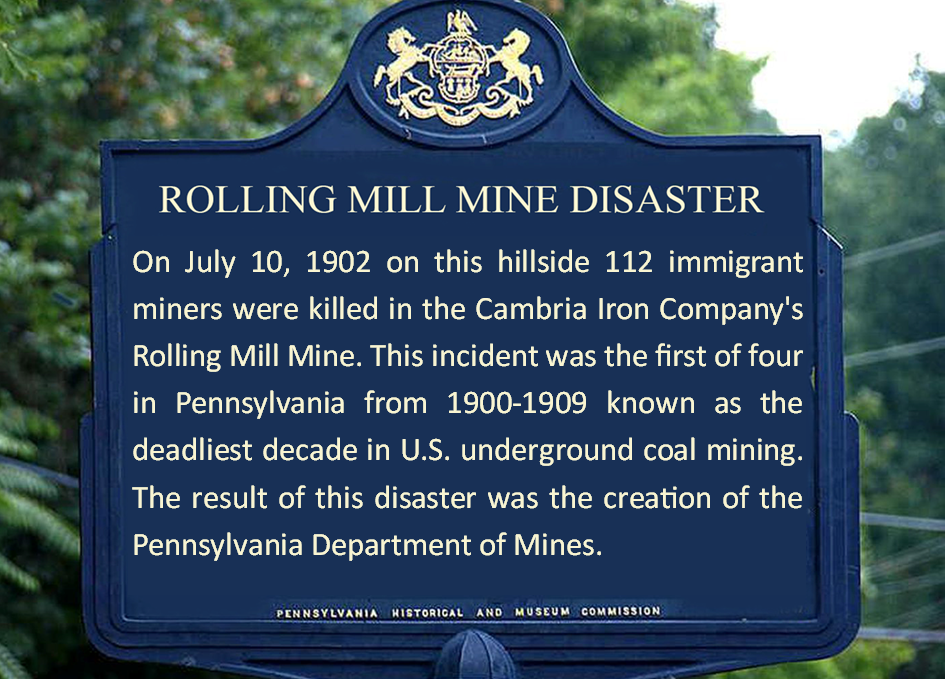

No one could have foreseen the series of events that would make the first decade of the 20th century one of the deadliest in the history of mining in the United States. The pivotal year was 1902 for several reasons 1) waves of immigration from Eastern Europe, 2) the Anthracite Strike in eastern Pennsylvania, and 3) the Rolling Mill Mine disaster in Johnstown, which resulted in the largest loss of human life to date in Pennsylvania.

In 1902, there were 648,743 new immigrants to the United States, mainly from Eastern Europe; these included persons from Poland, Czechoslovakia, Croatia, and Hungary.[2] These new immigrants found work in both the anthracite and bituminous mines in Pennsylvania. In the anthracite region this influx of cheap labor resulted in the Great Anthracite Strike of 1902 which was eventually resolved only through the intervention of President Theodore Roosevelt. The primary concerns of the union being that immigrants were not joining the union and presented problems due to language barriers and failure to understand mining rules and protocols.

The bituminous region of western Pennsylvania was also struggling with the influx of new immigrant labor. To demonstrate this impact, in the Cambria City neighborhood of Johnstown, within a 10-block area, there was St. Stephen’s church (Slovak), St. Mary’s (German), St. Casimir (Polish), St. Rochus (Croatian), St. Columba (Irish), and St Emerick (Hungarian). The majority of these new immigrants worked for the Cambria Iron Company in the Rolling Mill.

In the mill, it was the responsibility of the fire boss to check the mine for pockets of methane gas and to mark sections where there was gas so no one would work in the section that day. Likewise, miners were required to deposit any matches or smoking articles at the safety lamp station before picking up their safety lamps and entering the mine. Mining laws forbade the use of an open light in an area where gas was known to be detected. New miners were trained in the use of safety lamps and “notices of instruction in various languages were posted at the mine entrance and in other places” for miners to read.[3]

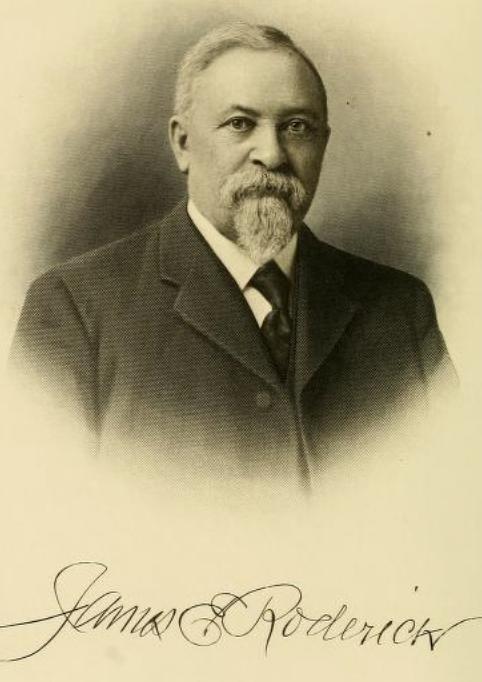

Source: Find-a-grave

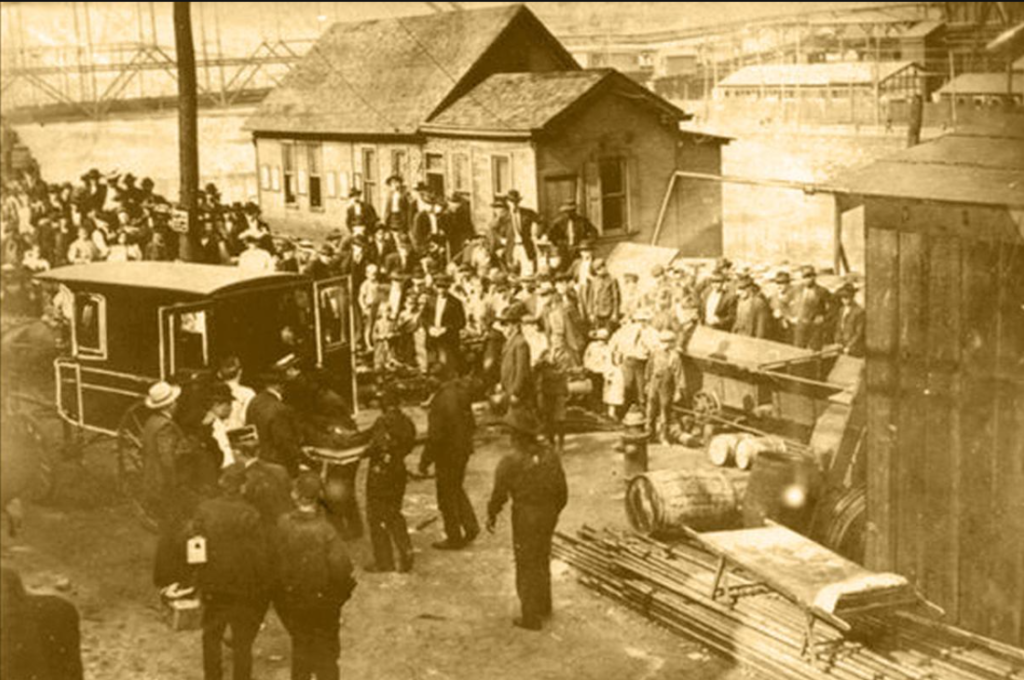

On the morning of July 10, 1902, several hundred miners entered the Main South Heading of the Klondike District mine owned by the Cambria Iron Company. At 11:30 a.m. there was an explosion. Immediately, Chief Mining Engineer Marshal G. Moore and his assistant, Al G. Prosser were the first to enter the mine. Using a safety lamp, the men were able to make it into the mine from the entrance but were turned back by the presence of “blackdamp” [blackdamp is an asphyxiant which remains after oxygen is removed from the air.] News of the explosion had reached the Bureau of Mines in Harrisburg who dispatched the Chief Bureau of Mines, James E. Roderick. Upon arriving in Johnstown, the afternoon of July 11th he stated, “The streets were filled with anxious and excited people, while in the street opposite the Rolling Mill Mine and at the entrance where the dead bodies were laid out they were nearly impassable. I mingled unknown with the sorrowful crowd that was viewing the dead bodies which were laid out in rows waiting to be identified by relatives and friends. Indeed, the scene was heart rending. I noticed that the great majority of the people viewing the bodies were people who did not speak one word that I could understand, but their grief touched my heart.”[4]

Courtesy Johnstown Area Heritage Association

Once arriving in Johnstown, Roderick knew that determining the cause of explosion would require additional assistance, so he sent for Inspector C.B. Ross of Greensburg, J.G. Roby, Uniontown, and Joseph Williams of Altoona. C.B. Ross of Greensburg had experience with miners who ignored the rules regarding open flames. In May 1902, in Commonwealth of Pa v Frank Canepeli, C.B. Ross prosecuted a miner who was guilty of having “a key then in his possession, unlock the safety lamp and light the same; and that the said lamp was kept open for some length of time and used as a common lamp, thereby endangering the lives, safety and health of person working in said mine.”[5]

After three days of inspection, it was determined that the cause of the explosion was a result of a miner using an open flame. In two locations, at the point of explosion, there was found on the ground a “miner’s open lamp filled with oil and cotton, ready for use, so this fall, which we learned contained fire damp…seemed to indicate that this might be the point where the gas was ignited.”[6]

On July 23, the final opinion was rendered, and it was determined that the cause was miner’s using open lamps. The inspectors then traveled to Pittsburgh where they were in session for two days and drafted a circular denouncing the use of open lamps and the specific mining laws that were violated [see Appendix A]. This circular was sent to all each mine foreman and superintendent of all the districts in the southwest.

The Rolling Mill Mine Disaster was the largest loss of life in a Pennsylvania mine up to that time. It set the precedent for mine safety and the use of open lamps by miners. The disaster was widely reported appearing in U.S. papers nationwide including The New York Times, internationally in Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia.

To address the fallout from the anthracite strike, the Rolling Mill disaster, and the competency concerns of immigrant miners, in January 1903, Senator Thomas (Schuylkill), introduced a bill in the Senate and House to replace the Bureau of Mines which operated under the Department of Internal Affairs and create a Department of Mines. While assuming the responsibilities of the Bureau of Mines, the new chief would be appointed by the Governor would need at least 10 years’ experience in managing, working and ventilating mines and shall have a theoretical knowledge of all noxious and dangerous gases found in such mines. The chief shall issue certificates to mine foreman and assistants in anthracite and bituminous districts and certificates of districts and certificates of competence to all miners who have passed a successful examination.[7]

The Rolling Mill Mine disaster resulted in the issuance of the Circular Letter by the Bureau of Mines and ultimately was a factor in the creation of the Department of Mines by the House and Senate; however, failure to adhere to the mining rules and guidance in the Circular, resulted in further loss of life in Pennsylvania mines over the course of the decade.

Sources:

[1] Bureau of Mines (1902). Report of the Bureau of Mines of the Department of Internal Affairs of Pennsylvania. https://archive.org/details/reportofbureauof1902penn/page/n103/mode/2up

[2] U. S. Commissioner-General of Immigration. … Immigration figures for 1903. From data furnished by the Commissioner-general of immigration. Comparison of the fiscal years ending and 1903. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.07902500/.

[3] Bureau of Mines (1902). Report of the Bureau of Mines of the Department of Internal Affairs of Pennsylvania. https://archive.org/details/reportofbureauof1902penn/page/n103/mode/2up

[4] Ibid

[5] Commonwealth of Pa v. Frank Canepeli, In the Court of Quarter Sessions of Westmoreland County, Pa. No. 20 May Term, 1902. C.B. Ross, Inspector, prosecutor.

[6] Bureau of Mines (1902). Report of the Bureau of Mines of the Department of Internal Affairs of Pennsylvania. https://archive.org/details/reportofbureauof1902penn/page/n103/mode/2up

[7] Legislature has mine measurers of wide scope (1903, January 23) Philadelphia Inquirer