Written by Jordan Shaw and Dr. Barbara Zaborowski

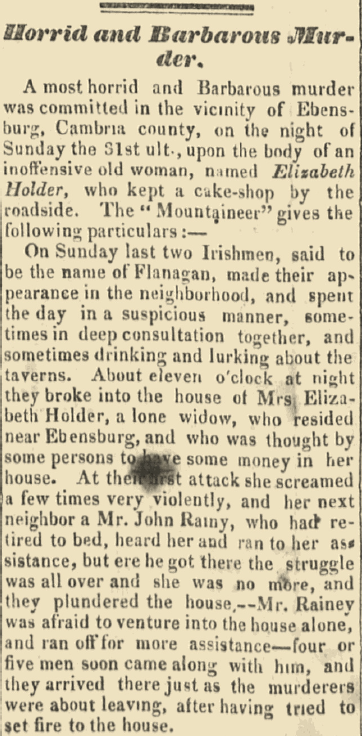

On an unseasonably chilly summer night in 1842, on a wagon-worn street heading eastward out of Ebensburg, Pennsylvania, two Irish immigrants were seen hurriedly leaving a quaint country log house belonging to a woman named Elizabeth Holder. Their exit was preceded by the echoing sounds of Elizabeth’s screams, which pierced the silent nighttime air and awoke several curious neighbors. A small group gathered and investigated the home, where they found the lifeless body of Mrs. Holder battered and draped over her broken down door, her blood and hair spattered around a large head wound, delivered by a pair of bloody tongs. They also stumbled upon a clock, stolen from its perch above Elizabeth’s mantle, her own blood used to crudely etch a message on its backside. This gruesome scene was the stage for one of the most notorious local murders in Cambria County’s history.

Elizabeth “Betsy” Holder was the youngest of five children born in 1786 to Jacob Yost and Mary Martha Holt in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. In 1803, the Yost family moved from Chambersburg to Munster but a few years later moved to a farm about two miles east of Ebensburg. On June 22, 1807, in Loretto, Father Demetrius Gallitzin presided over the marriage of Elizabeth to John Holder. Elizabeth’s mother died in November 1810, and in 1815, Jacob Yost, Jr. sold the 15-acre farm on the pike to Elizabeth and her husband.

By 1815, Elizabeth and John were parents to two children, John Jacob born in 1808 and Eliza born in 1809. Their happy family life was to last only five years, with both her husband and daughter having died by 1820. Elizabeth was left to raise her son on her own with the help of her family who had relocated to Carrolltown. By 1831, John Jacob at the age of 23, married Mary Josephine Lilly. With her son out of the house, Elizabeth was left alone.

In 1834, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania opened the Main Line of Public Works, which consisted of a series of railroads, canals, and inclined planes to transport people and goods across the state. To accomplish the feat of creating canals and laying rail lines, many Irish immigrants were used on the project. Two of those workers had been the brothers, Bernard and Patrick Flanagan. By 1842, the brothers were spending their time traveling around the central Pennsylvania area frequenting many of the local taverns and inns.

On the afternoon of July 30, 1842, the brothers were seen in the neighborhood of the Cottage Tavern in Huntingdon County, a few miles above Hollidaysburg and stayed at the tavern all night. Others in the tavern, heard them say they were on their way to Pittsburg to purchase horses. They were also seen at the summit, where they stated they were returning from Ohio. From the summit, they ended up in Munster and continued to make their way toward Ebensburg. Somewhere along the way, the brothers heard the story of a widow who lived nearby and had a stash of gold. Their final tavern was that of William Wherry, a neighbor of Elizabeth Holder.

William Wherry, the local innkeeper whose establishment was located near Mrs. Holder’s home, was among the small group that first discovered her body. He also was the first to alert the local authorities about this murder, and the two dark figures sporting Irish brogues that left Mrs. Holder’s cottage shortly before it.

A reward of $100 was offered for the arrest of the Flanagans. After an extensive search the Flanagan’s were caught and stood trial. The prosecution would claim that after drinking their fill and supposedly continuing onward to Ebensburg with their 19th century version of bar hopping, they made a stop at Elizabeth Holder’s home and murdered her in cold blood. During the eleven-day trial, the prosecution presented lengthy testimony from those neighbors who were awoken by Elizabeth’s screams, and by Dr. Aristide Rodrigue who examined the body, among others.

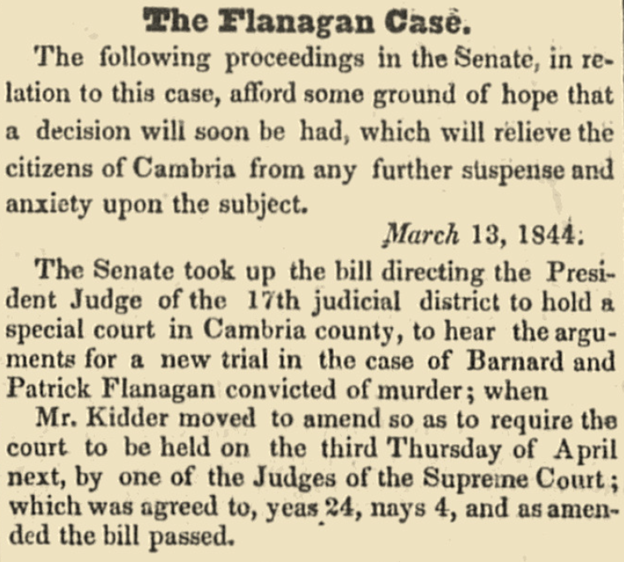

After eleven days, a jury pronounced the brothers guilty of murder in the first degree, and a sentence of death was received that same month, but the Governor, David Porter, sent a timely reprieve. A significant bit of judicial drama ensued, as the Flanagan brothers tried desperately to appeal this ruling. The initial appeal had been refused by both the local judge and the district judge who were loath to overturn the verdict of the jury trial but was then appealed to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, where a special counsel was appointed to oversee the notion of a retrial. There was a strong sense, especially among Irish immigrants and those sympathetic to them, that the initial trial was rushed, poorly run, and biased against Irishmen. Nevertheless, all appeals were declined, and it seemed all but certain that the order for the Flanagan’s executions would come swiftly.

Fate, it seems, had other plans for the Flanagan brothers. On the evening of the 7th of October 1844, Jane Flanagan, the sister of Patrick and Bernard, somehow obtained the keys to the room the brothers were imprisoned in, unlocked their doors, and proudly walked with them out of the jail, their hands still bound in irons. After sawing off their chains in a field a few hundred meters from their cells, Patrick and Bernard Flanagan disappeared from history, successfully escaping the final warrant for their execution by a few days. In the words of Dr. Rodrigue who later chronicled his involvement in this trial, “Thus ended a case which, for interference of legislatures, determination by some to shield the murderers, and the unpardonable negligence, to say the least, of officers, has no parallel in this country.”

Today, as in 1842, Americans are obsessed with the alluring mystery of murder. The events of Elizabeth Holder’s death so ingrained themselves into the local and state memories that, 40 years later, at the dedication of the newly built courthouse in Ebensburg, R. L. Johnston, Esq. recounted the murder, trial, and escape of the Flanagan brothers. The trial was so significant that being involved even merited a mention in your obituary. In the Ebensburg Cambria Freeman, on March 30, 1894, John Singer’s obituary identified him as “a juror and the last survivor in the celebrated murder trial of the Commonwealth vs. Bernard and Patrick Flanagan for the murder of Elizabeth Holder, which took place in October 1842, and which terminated in their conviction of murder in the first degree.” The case and its intricate and scandalous aftermath captured the attention and fascination of those living at the time, giving us a historical mirror of how Americans today are enraptured in the much more sophisticated major murder trials of today.

However, the disparity between criminal justice practices today and those of 1842 is extremely apparent. With modern technology and sensibilities, it is unfathomable that the sister of someone sentenced to death would somehow be able to charm away the keys, and successfully facilitate their escape. Criminal justice of the era had an extremely long way to go, and while still imperfect today, studying the practices of Betsy’s era shed a light on how much of justice we take for granted in our age.

This case also illustrates the anti-Irish sentiment existent at the time. The Flanagan brothers came to the United States before the Potato Famine, which would not hit Europe until 1845, yet the Irish still experienced enough discrimination that a major reason purported for re-trial was the alleged prejudices of the jurors. The Irish, like every group of immigrants to this country, would face an uphill climb on the road to cultural acceptance, and the actions of the Flanagan brothers was no great help to their compatriots who would soon flood Pennsylvania and the surrounding states.

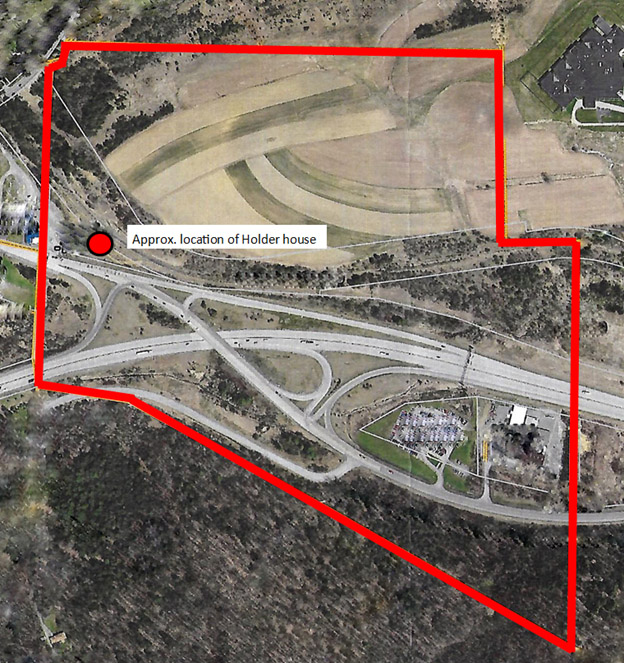

As all three Flanagan siblings withdrew from the recorded pages of history, so did the lives of the residents of Ebensburg continue. The property owned by Betsy Holder was sold by her son in March 1854 and included the small log house in which she was killed. At one point, tavernkeeper William Wherry, the neighbor who found her body, owned the property. Though her house is long gone, if you wish to visit the site of one of Cambria County’s most interesting murders, the property where it stood is located at the end of the Ebensburg/Loretto exit of Route 22 West.

References

Bernard and Patrick Flanagan. (1844, August 7). Tioga Eagle.

Governor Porter has signed the death warrant. (1843, January 18). Milford Jeffersonian Republican.

Horrid and Barbarous Murder. (1842, August 17). Huntingdon Journal.

Pennsylvania Legislature. (1844, January 24). Pittsburg Morning Post.

Rodrigue, Aristide. “Art. IX. — Contributions to Legal Medicine.” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences, vol. 20, Oct. 1845, pp. 338–355., https://doi.org/10.1097/00000441-184510000-00009.

Shocking Murder. (1842, August 20). Pottsville Miners Journal and Pottsville General Advertiser.

Singer obituary. (1894, March 30). Ebensburg Cambria Freeman.

Souvenir of Loretto Centenary. 10 Oct. 1899. pg. 235. “The Murder of Betsy Holder.” https://archive.org/stream/souvenirloretto00unknuoft/souvenirloretto00unknuoft_djvu.txt

To be hung. (1842, November 5). Bloomsburg Columbia Democrat.

Yost obituary. (1870, January 6). Cambria Freeman